Islamic Psychology: Answering the Ummah’s Distress Call

Reclaiming the Sacred Science of the Soul in an Age of Confusion

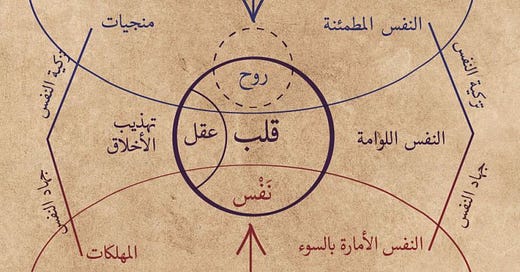

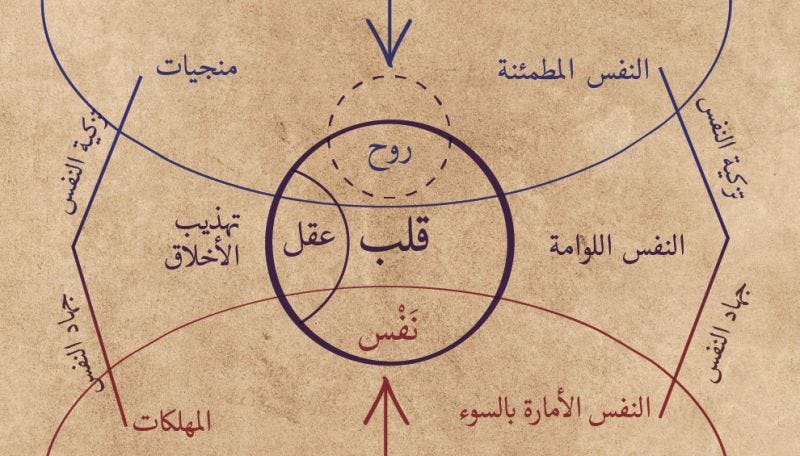

An Islamic model of the self: at the intersection of qalb (heart), ‘aql (intellect), nafs (self), and rūḥ (spirit) - illustrating the internal struggle between purification and ruin.

Patience and prayer, or cognitive behavioural therapy?

Meditation or enhanced engagement with the Qur’an?

A chemical imbalance or a spiritual malady?

Dopamine detoxing or greater focus in Salah?

Punishment for a life lived in transgression and disobedience, or just a lack of sunlight?

No Choice But to Wonder

Populations around the world continue to be plagued by mental health crises, and without significant course correction in sight, we can only forecast further decline. The same sickness of modern civilisation continues to indiscriminately corrode the human experience. I feel the collective human psyche is worn by the weight of its own errors, and Muslims are not immune to the effects.

Now and again I grab myself by the collar and pull myself into orbit, looking down at the condition we’re in, watching what feels like a race to remedy. A painfully slow race. The answers seem to me to not even exist within the same universe of urgency as they should. Some extra funding for therapists here, a few mental health awareness campaigns there - applying bandages to a ground rupture left by an earthquake.

If I had learned in a history lesson about a society where millions of people suffered from clinical depression and anxiety and other concoctions of mental illnesses, I’d wonder why they didn’t just… change things. The same should apply to the present time. The difference between a history lesson and our own lives is that we judge the former with clarity as we’ve seen its outcomes compressed in time, while our own lives move imperceptibly slow.

I give you the example of a person who eats sugar once and immediately breaks out in pimples, while another person eats 14 donuts a day for years and walks around with perfect skin. And guess which of the two are the subject of envy? The one whose body has accumulated the effects of a bad diet, except the effects are slow and internal. Slow decay doesn’t alarm us because it becomes entangled into the background of daily life. This is how habits become routines, routines become norms. And we all know even the most sceptical and discerning minds can struggle to spot faults in what’s considered ‘normal’.

You might suggest that we judge the past more easily because we’re spared the intricacies of that time. That may be true. To me, however, it’s more about the fact that we are not attached to their way of life, whereas we are our own. And this may be too dull and unremarkable an explanation, but it surely applies.

When it comes to our own way of life we are so attached to our comforts, routines and assumptions, that we refuse to make changes, even when it’s abundantly clear that modern lifestyles are not conducive for human, psychological and spiritual flourishing, no matter how many digital detox apps (downloadable on your digital device), standing desks, office plants, running clubs, and countryside retreats we’re sold. Anyways, that’s for another blog.

For years my own intrigue had led me down the road of Western Psychology but as a Muslim I would inevitably arrive at the junction of the Islamic Sciences. Better late than never. My journey thereafter would continue along a highway called Islamic Psychology - built on the principles of the Islamic faith, but also paved with the knowledge of Western Psychology.

Although having only recently entered this highway, I have already seen answers to countless questions that have followed me for years. In this blog, I hoped to present the emerging, revitalised discipline of Islamic Psychology as a meaningful response to the distress call of Muslims; particularly those residing in the West. I also want to acknowledge the role of ‘secular’ psychology in that regard, emphasising that the two are not competing forces but partners in the same pursuit. Finally, as always, I hope to offer some degree of remedial value in my blogs, and would never understate that said value could merely be in the form of understanding.

The Beginning: Why?

When a person suffers an affliction of the mind, questions about why they are suffering and how they should frame and conceptualise their experiences reverberate throughout the soul. This is because the insān (human being) has a spiritual predisposition to seek understanding of his condition. He journeys to enrich his perspective and colour his mind with knowledge of self and world, ideally to improve his life; the greater the need the more urgent the search.

Of all the phenomena experienced by the Creation, suffering is one of the most perplexing. We question ‘why’ as unconsciously as we breathe. It is in fact of the boundless Mercy of Allahﷻ that the very tests we face act as a compass which guides us towards the answer. Thus accompanied by this suffering is an innate drive to seek remedy; God did not prescribe suffering for the sake of suffering. That is the start. In Einstein’s appraisal: “The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution." Indeed, understanding is to mental turbulence what oil is to friction, and, more pertinently, nourishment for the soul. The Messenger of Allahﷺ taught us:

"When Allah wishes good for someone, He bestows upon him the understanding of Deen." [Al-Bukhari and Muslim; Riyad as-Salihin 1376, Book 12, Hadith 1]

The Distress Call

Muslims in the West - and no doubt, globally - are jointly acquainted with Islamic and Western nodes of thought. Each has its place in their lives, each calibrating their mind towards a fuller understanding of the context of one’s own life. Both contribute to the individual’s schema.

But what happens when a Muslim in the West begins to suffer from illnesses of the mind, or other ailments; who and what does she turn to? Which system of thinking and living and being does she draw recourse to? Which forms of remedy are permissible, and which trespass into the prohibited? A simple enough set of questions, with a simple enough answer: she turns to Allahﷻ.

And thereafter one might assume a linear path to improvement.

It is not, however, this simple. A Muslim may very well know that he must turn to Allahﷻ in times of distress, yet remain uncertain about what form that turning should take. He is surrounded by an abundance of information on mental illness, diagnostic frameworks, and therapeutic options. But the most specialised and seemingly robust literature has been - like many Muslims themselves - born in the West. It is literature shaped by the cultural assumptions and epistemic commitments of a secular-modern society, rooted in a worldview where the human being is often reduced to mind and body, and where the goal of life is framed in material or psychological terms.

The result is a subtle dissonance: while there exists a vast reservoir of knowledge from which one may draw insight or intervention, the medicine on offer is constrained by the very psyche that produced it.

It is constrained because the worldview it reflects is, to the Muslim lens, not only incomplete but, in essential respects, misdirected. It does not account for the spiritual reality of the human - for the qalb, the nafs, or the ruh, each a distinct axis in the architecture of the self. Even when the intellect (ʿaql) is acknowledged, it is often treated as an isolated cognitive faculty, whereas in Islam it is guided by the qalb. It’s akin to a mechanic refusing to acknowledge the existence of an engine while diagnosing a broken car. Instead, he obsesses over the tyres and hydraulics. He installs a set of Michelin Pilot Sport 5s, renowned for their grip and traction in the wet. But the car still doesn’t run.

Consideration of the heart as anything beyond a storage of feelings and emotions is outside the purview of Western Psychological medicine and treatment. The explanation for this is manifest: the prevailing framework for ascertaining the truth in the West, the highest epistemic authority, is the scientific and empirical method, from which it is then consistent that the role of the heart - the emotions from which are impossible to measure - should be ignored. Its role within the Islamic framework, on the other hand, is incalculably more vast and significant. The Qur’an presents the qalb not just as the seat of emotion or moral intuition, but as the locus of the cognitive and intellectual faculties; particularly perception.

"Indeed in that is a reminder for whoever has a heart (qalb) or who listens while he is present [in mind]." - (Al-Qur’an, 50:37)

This framing suggests that the qalb is more than a metaphorical heart; it is a spiritual-intellectual centre through which truth is either received or rejected. Although the ‘aql (intellect) is usually linked to reasoning, in Islam it’s the qalb (heart) that leads and directs it, meaning that our thinking is meant to be guided by spiritual awareness. For this reason Dr Utz describes it as the ‘super-sensory’ organ.1

Revisiting the dilemma, the burden doesn’t cease to grow. The Western Muslim knows he would be ill-advised to completely reject the knowledge offered by the secular world of psychology, even if it operates within a paradigm largely unhelpful to his existential reality. Yet, he has felt wounds upon his soul; wounds far more profound than the bruises left by the bio-physiological blows of modern diagnostics. His intuition recoils at the thought of administering a medicine for the body in place of a medicine for the soul, and expecting harmony to follow. To use science as a remedy for a spiritual affliction feels almost blasphemous. Yet the Qur’an - perfect, timeless, and unmatched in spiritual depth, and the Sunnah - the living embodiment of its principles through the words and actions of the Prophet ﷺ - without careful interpretation and contextualisation, do not always seem to offer the specificity of advice he seeks.

Summarising the Predicament

For the Muslim in distress, the crisis often isn’t just emotional or mental. It’s epistemic, and they might not be conscious of this. What to trust, what to turn to, what even counts as ‘help’. A blur between the sacred and the clinical, between dua and diagnosis. The Muslim is unsure what door to knock and, when she knocks, which framework will open it? There is fear in turning to what’s outside the tradition. Fear that it betrays faith but also doubt that the tradition, at least as she has inherited it, is enough. Then rolls in the whisper that therapy is for the weak. That reciting Qur’an without feeling relief means something is wrong with one’s imaan. A believer may also be troubled by the misconception that worship is only sincere and acceptable if offered in a state of high spiritual feeling. These thoughts swirl, reverberate, compound. The lines blur, and then disappear, leaving confusion lingering in silence.

In the following list I’ve compiled just some of the confusions and distresses that Muslims - particularly in the West - may face in their mental health crises:

Uncertainty about where to seek help – Unsure whether to turn to religious sources, therapy, or medicine

Confusion over what counts as valid knowledge – Don’t know what Islam permits or prioritises

False split between Islamic and secular knowledge – Thinking anything not labeled “Islamic” must be rejected

Forgetting Allah is the source of all knowledge – Overlooking that truth, wherever found, is from Him

Fear of betraying the religion – Feeling guilty turning to anything outside traditional religious practice

Over-reliance on ritual – Thinking that dua or passively reading Quran alone is enough, without reflection or change

Disconnect from Islamic scholarship on psychology – Unaware scholars have long dealt with mental health through Islam

Internalising secular worldviews – Accept materialist ideas without realising they conflict with Islamic principles

Fragmented view of the self – Don’t know how nafs, qalb, aql, and ruh work together in Islamic thought

Suffering in silence – Stay quiet out of shame, assuming their struggle is a sign of weak faith

In Conversation with Western Psychology

It must be stated from the outset that the most significant contributions to modern psychology have been from the West. From theories of the mind to empirical and clinical research, we are all beneficiaries of the knowledge refined by modern Western thinkers, regardless of their religious orientations. The purpose of this piece, and indeed of Islamic Psychology, is not to reject or diminish that work, but to complement it. Western psychology often ends where the Islamic tradition begins. Rather than discarding it, Islamic Psychology takes from it what aligns with its worldview - crucially, not the inverse - and reorients the rest towards a God-centred understanding of the human being.

Truth, Tradition, and the Search for Wholeness

Minds throughout history have grappled intellectually to understand, define, and explain the human condition; to fully comprehend who we are, why we are here, where we came from and where we are going. While this endeavour has borne some fruit, it has remained, time and time again, an insatiable pursuit. That is, except and until there is recourse to Islam; a belief in the existence of One God, the acknowledgement that He is the highest epistemic authority, and that His Word is complete and infallible.

Without the belief in an objective truth, which guides our intellects and transcends the time and context of the physical realm, the pursuit to understand the human condition will yield either false results or an incomplete truth. Full remedy will never be achieved without recognising that the soul exists, and understanding its nature and components. To that point, secular therapy and other remedies will only afford you limited relief, depending on the ailment. Indeed, that relief may be real and rooted in knowledge which is in alignment with the laws of Allahﷻ, but total alleviation will come only from understanding that Allahﷻ made us, and that following His laws to the best of our knowledge and abilities is what leads us to wholeness.

The Answer

As far as the epistemic crisis concerned, the guiding principle is simple and it steadies us: truth isn’t in the form - it’s in the source.

Allah ﷻ says, “Say: ‘It is from your Lord — the Truth.’” (Qur’an 10:108). Imam al-Shafiʿi رحمه الله put it plainly: “Whatever aligns with the Qur’an and Sunnah is to be accepted - even if it comes from the East or the West.”

Truth doesn’t speak one language. It doesn’t need a label. What matters is alignment with revelation, with tawḥīd, with the fitrah (God-given disposition)..

Islamic tradition recognises that the soul (ruḥ), while pure in its origin and divine in its essence, is experienced through the self (nafs), which undergoes varying states and transformations. The Qur’an outlines three primary stages of this journeying soul: al-nafs al-ammārah (the commanding soul), al-nafs al-lawwāmah (the self-reproaching soul), and al-nafs al-muṭma’innah (the tranquil soul).2 These are not rigid categories but flowing states of being which reflecting the soul’s proximity to truth, its alignment with divine guidance, and its success in subduing the lower self. Each stage has its own inner climate, patterns of thought, and psychological symptoms. Each demands its own treatment.

The commanding soul (al-nafs al-ammārah) is impulsive and untamed; it commands evil, normalises disobedience, and resists discipline. It is the soul that has been overtaken by the lower self and the whisperings of Shaytan. The reproachful soul (al-nafs al-lawwamah) is self-aware, remorseful after wrongdoing, and engaged in moral struggle. It is the battleground of conscience. Finally, the tranquil soul (al-nafs al-muṭma’innah) is the soul at rest - purified, surrendered, and content with the decree of Allahﷻ. It is the soul addressed in the Qur'an:

"O tranquil soul, return to your Lord, pleased and pleasing..." (Al-Qur’an, 89:27-28).

True psychological healing, in the Islamic sense, is not merely about symptom management, it is the ascent of the soul through these states, the gradual movement from chaos to serenity, from disobedience to alignment, from fragmentation to wholeness.

The believer must perceive the world with the nur (light) of the Qur’an and Sunnah illuminating on it, to ensure sound interpretation of epistemological truth, so that he or she can select the Islamically correct course of healing. All knowledge, whether collected via Revelation, Hadith, intuition or experimentation, is from Allah who is Al-’Alim (the All-Knowing). In this light, what we pronounce as “un-Islamic” knowledge need not be rejected but rather embraced as it is just another means through which Allahﷻ has delivered us healing, in a way perhaps which makes understanding the Qur’an and Sunnah easier. The only criteria is that those means to achieve healing and tranquillity do not contradict the laws of Allahﷻ.

This understanding is not new. Scholars like Imam al-Ghazali and Ibn Rushd engaged deeply with the philosophical and medical traditions of their time, drawing from Greek thought not because they saw it as religious, but because they saw in it tools that could serve the truth. More recently, contemporary scholars and practitioners of Islamic psychology - such as Dr. Malik Badri, Abdallah Rothman, and Aisha Utz - have affirmed the legitimacy of drawing upon modern psychology as long as its theories and interventions do not violate the core ethical and metaphysical foundations of Islam. This means that therapies based on empirical research, behavioural conditioning, or even neurochemical understanding may be employed, provided they do not conflict with the Islamic view of the human soul and / or morality. Just as we do not reject Western medicine when treating the body, we are not required to reject it when treating the mind, as long as the soul remains rightly framed in the process.

The foundations of Islamic psychology were not born recently, they were formulated and refined by the early scholars, and their source material, the Qur’an and Sunnah, will continue to stand the test of time until time itself ceases to exist. The manual has remained unaltered, and this tells us something essential about the nature it addresses: the human being. As long as that nature remains constant, the guidance revealed for it will never fail nor become deficient in leading us to the Last Day.

The believer should be reassured that all the questions posed at the beginning of this blog are not ones she must burden herself with. Within the confines of permissibility - clarified, if needed, by those more knowledgeable - she may pursue therapies and other remedies not directly born out of the so-called Islamic tradition.

Yet, a Muslim would also do well to remember that suffering is not always meant to be solved, but sometimes simply endured. Its purpose may not lie in intellectual resolution, but in the cultivation of sabr. When we think of what the lesson could be, we think semantically, rather it could be a state we must attain. At your lowest point dwells a divine invitation to ascend to the highest spiritual point, by choosing whether to persist in relying on your limited, fallible understanding, or to surrender your burden to Ar-Raḥman, the One who provides before we ask, forgives beyond what we deserve, and responds to duas our hearts and tongues aren’t steady enough to form. In that surrender lies the true test: of trust; and, the essence of Islam: submission.

The Inner Struggle and the Return to Tawakkul (trust)

Waxing and waning, the war that is life occupies us constantly. Sometimes it gets the better of us, and in our distress we forget why we are here. As the waves of our trials begin to drown us we implore every atom in our bodies towards the motion of reaching safety. Relying on ourselves, our intuition becomes blunted, unable to remember that the purpose of this life is not this life itself, but the everlasting one. As much as we want to exercise control over it, our greatest hope is in seeking refuge in Allahﷻ - and relying on Him instead.

We have a proclivity to overcorrect our reliance on intellect, and flow into the realm of over-reliance, where reason becomes our only tool. We should instead be practising Tawakkul (absolute trust and reliance upon Allahﷺ)

“And whoever relies upon Allah – then He is sufficient for him.” (Al-Qur’an, 65:3)

Modern psychology and neuroscience have, through their own means, reached some of the same conclusions presented to us 1400 years ago through the Holy Qur’an. The same advice is offered in different packaging, more palatable to a society which believes only in truth derived from lived experience. It encourages mindfulness, a return to simplicity, a focus on what is within one’s control and a regulation of worry and rumination. All things rightly considered, but formed on understandings of the self which do not even acknowledge the soul and therefore are - in the Islamic view - incomplete.

First, correct your heart

We can learn something further from the wisdom of the Prophet ﷺ:

“Truly in the body there is a morsel of flesh which, if it is sound, the whole body is sound; and if it is corrupt, the whole body is corrupt. Truly, it is the heart.” (Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, 52; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 1599)

In my view, this message is too often taken as purely metaphorical; and undoubtedly I’ve been among the guilty in that regard. But with a holistic understanding of what the qalb is, its functions and interrelations with other core components of the self (nafs, aql, and ruh), it becomes clearer that engaging in anything that displeases Allahﷻ is not just spiritually detrimental, but harms us cognitively, physiologically, emotionally, even neuro-chemically.

Concepts such as chronic guilt, shame, stress, anxiety, hopelessness, detachment from self, social exclusion, and emotional numbing have been extensively studied in modern psychology, and not merely as passing moods, but as states that can give rise to internal, physical strain. These conditions, often the result of persistent moral misalignment, actions prohibited in the Divine Law, place a continuous pressure on the nervous system.

Over time, this dysregulation can compromise the immune system, leaving the body more vulnerable to illness. It is not difficult to see, then, how the effect of sins manifest in the body, the mind, and one’s overall sense of stability.

This is why, in the Islamic tradition, the response to sin is not just guilt, but Tazkiyah - the purification of the heart, through sincere repentance and dhikrullah (remembrance of Allahﷻ).

The qalb is the filter through which truth is recognised and acted upon. Thus, even with knowledge at our fingertips, we will remain unable to act in the right way unless the heart is rightly aligned.

Hope in Islamic Psychology

Although you may not have heard of it as a discipline, Islamic Psychology is not new, its roots trace back over a thousand years, but its current revival and academic formalisation is still in its infancy. Figures like al-Balkhi and al-Razi addressed mental and emotional states in holistic ways, centuries before psychology emerged as a modern discipline. The changes in the nature of the world have been felt by humans in a profound way; and never in history have human lifestyles been so disastrously misaligned with their nature. Clinical psychologist Dr Stephen Ilardi frames that the world has undergone a radical environmental mutation in the last 200 years, and that depression is a ‘disease of civilisation’.3 I could not agree more.

As the world continues to develop, pedalled by the motivations of material progress but devoid of metaphyisical anchoring, modern, secular societies will struggle in grounding their reality or morality in anything substantial. This will be to the detriment of the secular psyche as a collective but will also damage the individual, leading to an even wider web of mental health crises than what sadly exists today.

As Muslims, we hope and should labour to circumvent this. Our traditions are rooted in physical and metaphysical reality. It is up to us to adhere precisely to the manual Allahﷻ has given us, while the rest of the world follows their own lines of enquiry, albeit with some, limited success. On this path, however, we cannot trivialise or dismiss on the contributions of the Western World, to which many of us ourselves belong. So much is owed to the minds and institutions that have advanced our understanding.

It falls on us to drink from the source of Truth, to translate it and reconfigure it within whatever context it may be needed. Our hope is to become sources of help for Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

¨Your heart is a polished mirror. You must wipe it clean of the veil of dust that has gathered upon it, because it is destined to reflect the light of divine secrets.¨

- Imam Al-Ghazali

Thank you for reading.

السَّلاَمُ عَلَيْكُمْ وَرَحْمَةُ اللهِ وَبَرَكَاتُهُ (Peace be upon you, and the mercy of God and His blessings)

Utz, A. (2011). Psychology from the Islamic perspective. International Islamic Publishing House.

Utz, A. (2011). Psychology from the Islamic perspective. International Islamic Publishing House.

Ilardi, S. S. (2009). The depression cure: The 6-step program to beat depression without drugs. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Such a well-articulated, enlightening, and necessary piece. Thank you!

Extremely well-written, Arslan. Very on point!